When AI Systems Fail: The Toll on the Vulnerable Amidst Global Crisis

By Nadah Feteih

Nadah Feteih is currently an Employee Fellow with the Institute for Rebooting Social Media at the Berkman Klein Center and a Tech Policy Fellow with the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley. She holds B.S and M.S degrees from UC San Diego in Computer Science with a focus on systems and security. Her background is in privacy and trust & safety, working most recently as a Software Engineer at Meta on Messenger Privacy and Instagram Privacy teams.

This piece first appeared on the Tech Policy Press website on November 7, 2023.

Reactive measures to address biased AI features and the spread of misinformation on social media platforms are not enough, says Nadah Feteih, an Employee Fellow with the Institute for Rebooting Social Media at the Berkman Klein Center and a Tech Policy Fellow with the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley.

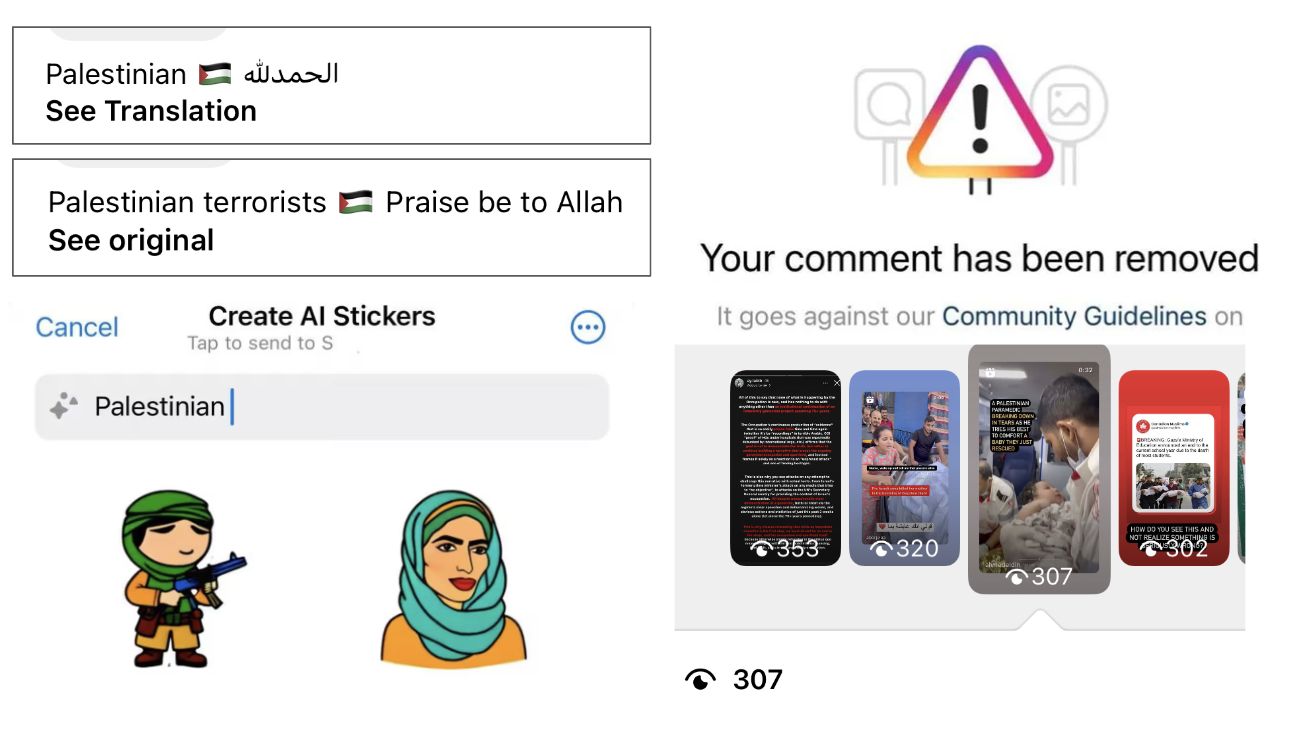

Examples of mistakes in AI stickers, auto-translations, and content moderation decisions.

Social media is vital in enabling independent journalism, exposing human rights abuses, and facilitating digital activism. These platforms have allowed marginalized communities to reclaim the narrative by sharing their lived realities and documenting crises in real-time. However, decisions made by social media companies chiefly prioritize profits; tackling integrity issues and addressing technical problems that further the spread of harmful content appear to be at odds with their incentives. While there may be tension in reconciling user expectations and features motivated by platform business models, users and tech workers exceedingly feel silenced from biased mistakes made during times of crisis. The stakes are even higher when these mistakes subsequently exacerbate real-world harm.

Consider two recent examples, both of which involve technical “errors” in Meta products that resulted in dehumanizing misrepresentations of Palestinians amidst the ongoing situation in the region.

The first instance was reported on October 19 by 404 Media. When users had text in their bios that included “Palestinian” and an Arabic phrase that means “Praise be to God,” Instagram auto-translated the Arabic text to “Palestinian terrorists.” The company corrected the problem and apologized for the error.

Then, on November 2, the Guardian reported that when variations of the terms “Palestinian” and “Muslim” were searched in WhatsApp’s new AI Stickers feature, images of children with guns were returned. According to the report, “Meta’s own employees have reported and escalated the issue internally,” and a Meta spokesperson blamed the incident on the generative AI system powering the feature. The AI stickers are generated using Meta’s Llama 2, an open source large language model, and Emu, a new image generation AI model. Along with the release of Llama 2 and the new stickers feature, the company made a commitment to the responsible development of LLMs as it made the software available to the research and development community.

While prompt remediation, apologies, and quick fixes are important, it is necessary to dig deeper into whythese errors occurred and ensure appropriate guardrails are established so other harmful technical mistakes don’t make their way into production. These models function in ways that rely on corpuses of user generated content from the internet and from these social media companies' own platforms. Research has suggested this leads to embedded bias and downstream results that perpetuate harms towards marginalized communities. If there is an influx of hate speech and incitement on these platforms, how can we be certain it doesn’t emerge from or creep into training data that is used by AI systems? Societal ills, bias, and racism are amplified by generative AI technology, and when combined with the scale of social media platforms, the results can spread quickly online, introducing even more risk to groups facing imminent threats.

There is widespread acceptance across the industry that generative AI systems will have inaccurate and biased results based on the datasets they have been trained on. This appears to be an acceptable risk for Meta- its spokesperson pointed out to the Guardian that it had anticipated such problems when it launched the stickers feature. “As we said when we launched the feature, the models could return inaccurate or inappropriate outputs as with all generative AI systems,” he said. “We’ll continue to improve these features as they evolve and more people share their feedback.”

But these features shouldn’t remain on the platforms while they “improve.” Releases should be put on pause until they can ensure fair and accurate results.

It’s important to point out that these two instances were identified and reported by Meta employees that experienced these issues first-hand and are part of the communities that are disproportionately affected by these mistakes. Over the last few years, we’ve seen tech workers rally together to speak openly and engage in internal escalations to address issues as they develop. While this approach leads to small wins in bringing back posts, removing doxxing content, and reversing false positives in content moderation decisions - this can never be a sustainable model to address future crises. We’ve seen in the last few weeks a rise in misinformation through deepfakes, unverified claims spreading like wildfire, and a massive drop in content reaching individuals. Many social media platforms appear to be scrambling to address issues as they come in - a “fighting fires'' response that we’ve seen repeatedly whenever a crisis emerges.

Social media companies have publicly made commitments to social good, integrity, and privacy teams, yet these are the first departments that are cut and underfunded during difficult times. The teams that are integral to addressing ethical issues should be allotted the necessary resources, investment, and should prioritize long-term roadmaps to systematically address these issues. While underrepresented employees at the company provide valuable perspective and context which helps identify problems affecting their communities, their reports and personal escalations should not replace sufficient testing and red teaming to find and fix issues preemptively.

When vulnerable groups such as Palestinians are faced with unprecedented violence, genocide, and ongoing atrocities affecting their daily lives, it requires efforts and coordination from all different sides. Journalists that leverage platforms to share raw footage of the realities on the ground need their accounts protected, civil society groups that collect reports and produce research that consolidate major issues need clear channels to raise these demands, and tech workers that are embedded within the communities that are severely affected should have an avenue to ensure their voices are heard within their companies without the fear of retaliation and internal censorship.

In times of emergency and a humanitarian crisis, social media platforms should be held to a higher degree of accountability and begin addressing these issues through foundational measures rather than hotfixes.